Mkinvartsveri | Kazbek (5054 m)

First Ski Descents and the Road of Dreams

February 2019. It is a stormy winter day at 3000 m in the Georgian Caucasus. A dog looks at me as if he knows me, as if I have been here before. In the background, Mkinvartsveri (5054 m) rises, the sun shining on the upper slopes of the southeast face. Somewhere up there, my fascination with the Caucasus started. First, with an image of these slopes in my father's geology book, my fingers tracing lines up and down snowy slopes and ice faces; later, standing with skis at the drop-in to my dream line—the SE face direct, or “3B”. The pursuit of skiing this and other lines on this beautiful peak would lead me back to Georgia year after year. However, it was not just about the mountains. It was the unique mix of mountains, culture, immense hospitality, and the chaotic, charming, and vibrant Tbilisi transitioning into a modern future.

In 2008, I skied the SE face direct (50°+) with Andi Riesner and several other new steep routes. In May 2013, I returned to Mkinvartsveri one more time to climb and ski the last unskied line. Trevor Hunt, a Canadian steep skiing legend, and I ascended the rarely climbed Japharidze ridge and N-NE face to the summit in less than three days. Together with Georgian climbers a few weeks before us, we are the first people to climb this route in over 50 years – and the first to ski it. This descent was the fourth steep line I skied in the course of seven years. A full article can be found at ︎Mountain Life.

In 2017, I returned to the area with three Ukrainian friends, climbing Mkinvartsveri`s neighbour peak Maili Khok (4600 m). Some refer to the route along its ridge and onwards as the "Road of Dreams". It was a memorable climb during a time when the mountains of the Caucasus seemed to have no borders. Little did we know about what would follow and how plans and dreams would vanish because of decisions made by men.

Today, I live part-time in Georgia. The image of Mkinvartsveri from February 2019 hangs in my living room in Norway. The print was a present from my wife, whom I had met in Georgia. We got married a few months after I took the image.

Pik Pobeda East (6762 m) — The First Ski Descent

Skiing my dream line in the Kyrgyz Tian Shan

In the summer of 2010, Anders Ödman and I traveled to the Tien Shan mountains of Kyrgyzstan. After the first ski descent of Shkhara (5193 m) in the Georgian Caucasus, I wanted more – a long, sustained, and aesthetic ski line on a major peak.

Our initial goal was the north face of Pik Pobeda (7439 m), but the warm and wet July and serious avalanche hazard made an attempt unreasonable. After days of scouting, studying maps, and analysing old images, we identified two potential lines: the aesthetic northeast ridge of the remote East Summit (6762 m) and the southeast ridge of Pik Voennizh Topografov (6873 m).

A few days later, we began the multi-day approach up the Zvezdochka Glacier, skinning into a world of ice and snow far removed from the usual base camps, traversing beneath the 2500 to 3000 m high meter north face of Pik Pobeda. The sound of avalanches was frequent, with proportions of which they we had never seen before or would see since. One morning, a powder cloud from a massive slide whipped over our tent at 4800 meters, an explicit reminder of how powerful the mountains here are and how small and vulnerable we are.

Several days after leaving base camp, steeper terrain led us to the Chon Teren Pass (5450 m) below Pobeda East and Voennizh Topografov. From here, it is clear that the ridge of Pobeda East is continious, almost perfect ski line.

After sitting out a storm, we began the ascent of the NE ridge – up to 50+° steep – toward the east summit of Pik Pobeda. Anders turned back 200 vertical meters below the summit, conserving energy for a safe descent. I continued alone, battling wind slabs, crust, and loose snow over rock.

Exhausted, I reached the summit at 14:30. To the north lay China; to the south, the vast Kyrgyz Tien Shan. The scale of the mountains was unlike anything I had ever seen. With time slipping away, I snapped a few summit shots with my trusted Contax T3, clicked into my skis, and descended back to our tent on the pass. The first turns on wind slab cautious, later the flow came.

A lone ski descent, down a logical line.

The NE ridge of Pik Pobeda East is likely the biggest line ever skied in the Tien Shan – and my finest. A short article on the descent is found in the >> AAJ.

Pik Chapaev (6371 m)

One of the most beautiful peaks

Prior to skiing Pik Pobeda East (6762 m) in the Kyrgyz Tian Shan, we acclimatized on Khan Tengri (7010 m) first. The views toward Pik Chapaev, an elegant, airy ridge above the clouds, were stunning. In that moment, it was the most beautiful mountain I had ever seen.

Chatyn-Tau (4412 m) - the 1st Ski Descent of the SE Couloir.

Chatyn-Tau is a 4412 m high mountain in Svaneti, Georgian Caucasus. Three summits give it a distinctive, impressive shape. Still, the peak stands in the shadow of its famous neighbour, Ushba (4710 m). Still, Chatyn-Tau holds some of the best steep-skiing lines in the Caucasus. One is the large Southeast-Couloir of the West Summit (4310 m), clearly visible from Mestia. Since my first trip to Svaneti in 2010, the couloir had been on my mind.

In May 2013, just days after the first ski descent of Mkinvartsveri`s NE face, Canadian steep skier Trevor Hunt and I arrived in Svaneti. With a lot of ice on the large south-facing walls of Janga-Tau and Shkhara, we turn our attention to the SE couloir of Chatyn-Tau. 1800 m vertical, wild bergschrunds and crevassed at the bottom, seriously steep and exposed at the top.

The surface was hard; deep runnels covered the middle section of the couloir. The sheer size, combined with the hard conditions and misty weather, gave the route an uncomforting, heavy aura. The ski descent ranks perhaps as my hardest and scariest. A thin snow cover on ice, 55° and more. A day later, we skied the SW face. Both would be my last steep ski descents in the Caucasus. Four years later, Miroslav Peťo and Maroš Červienka repeated the line in better conditions. They rated the route at Traynard S5/S6, E3, 50-55°. ︎Link to report

A full article can be found over at ︎Mountain Life.

Bezengi Wall - One Day...

In June 2010, Boris Avdeev and I stood on top of Shkhara, a 5193 m high, challenging summit in the Caucasus. Shkhara is the highest point of the Bezengi Wall, a 12 km long mountain massif largely above 4500 m along the Georgian-Russian border. Shkhara also marks the eastern end of the wall and is either the last or first summit of the Bezengi traverse – a traverse of the entire massif over multiple 4500-5000 m summits and one of the greatest alpine challenges in the Caucasus and Europe. A few weeks later, Boris writes to me - “one day, we have to do the traverse”. This day will never come. Boris perishes in an avalanche in April of 2012. We were to climb Janga-Tau (5058 m), a remote peak seldom climbed in the central part of the Bezengi Wall, a few weeks later. After two months in a mental hole, full of doubt about the sense of going to the mountains, and filled with a lack of motivation and self-discipline, I travelled to Georgia again. On 22 June 2012, I summit Janga-Tau with Robert Koschitzki. As I sit on the summit and watch Robert coming up, I look to great Shkhara rising behind him, where Boris and I stood two years earlier, and then look behind me to the remaining summits of the Bezengi wall to the West. I wonder if I will ever make the traverse. Maybe, one day...

(LFI Mastershot. Published on the Leica Fotografie International Blog, One Photo, One Story)

Documentary/Reportage Work

During 2011 and 2012, I worked on several photo projects in the South Caucasus, mainly covering the aftermath of the Abkhazia, South Ossetia and Karabakh wars. It was a sobering experience. Yet, despite all the misery, I also experienced tremendous hospitality from the internally displaced people (”IDPs”) and refugees, sharing whatever little they had. We talked, drank and ate together. It was a memorable time, and I am grateful to the Norwegian and Danish Refugee Councils and UNHCR Armenia for giving me the opportunity for these projects. Some things may have changed, but the recent flare-up of the Karabakh conflict shows that some things sadly have not.

Early Winter in Ergneti

(2011)

In the autumn of 2011, I began working on my long-term photo project about refugees and internally displaced people in the South Caucasus, working closely with the Norwegian and Danish Refugee Councils. During my work, I also visited the Georgian side of the buffer zone to South Ossetia. In 2008, a conflict erupted between Georgia and Russia over the breakaway region of South Ossetia. When I arrived in Ergneti, the war had been over for more than three years, but there were still traces of it everywhere – not only on the houses and infrastructure but also in the minds of the people living there. One scene struck me in particular: a lonely, elderly woman walks down a muddy street as winter arrives in Ergneti, a town almost completely destroyed during the war. The losers of this political power game are the people living on either side of the buffer zone – people who lost wives, husbands, sons or daughters, who lost their homes and livelihoods amidst the shelling, burning and bombing of villages.

The images were taken in 2011 during a photo project in collaboration with the Danish Refugee Council (DRC).

Tskhaltubo/Georgia - Waiting Since 18 Years For …?

(2011)

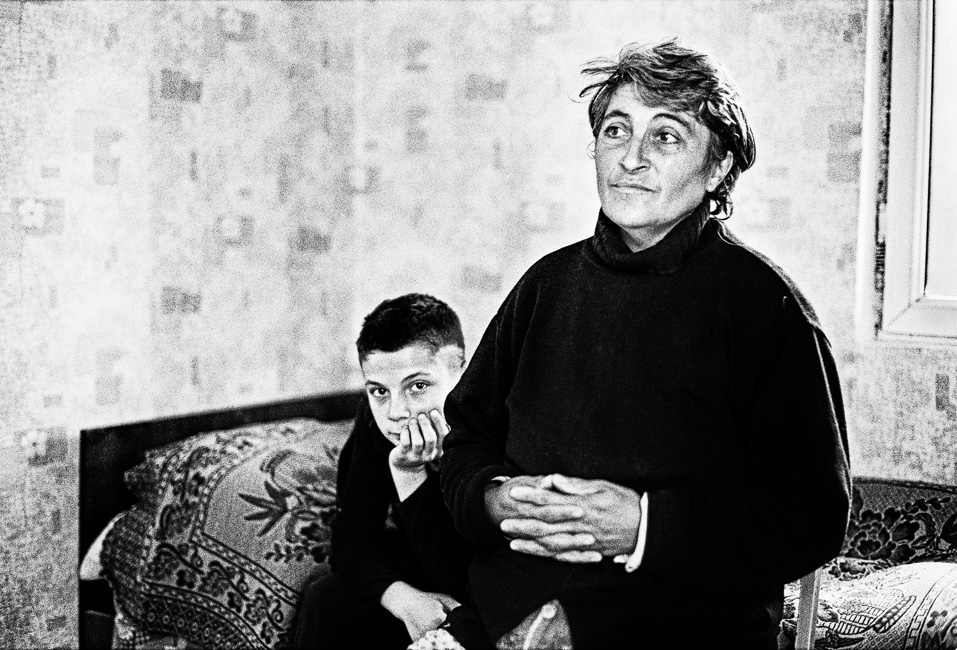

Tskhaltubo, a former Soviet spa resort, is now turned into a shelter for internally displaced people (IDP) from the short but intense Georgian-Abkhaz wars (1992–93 & 1998). The conflicts resulted in numerous war crimes, massacres and ethnic cleansing, forcing around 250,000 ethnic Georgians to flee Abkhazia. Some 7000* IDPs have been living here for 18 years in poor, cramped and unsanitary conditions, waiting for another future, seemingly forgotten by the rest of the world.

Tskhaltubo’s dilapidating buildings used to be the Soviet holiday paradise. Now, they are haunted by the ghosts of the past and the broken hopes of the present.

The images were taken in 2011 during a photo project in collaboration with the Danish Refugee Council (DRC).

*This number has decreased to 800 due to efforts to resettle IDPs in proper homes. Photo project from 2018 by Ryan Koopman: >>Sanatorium

Refugees in Armenia - Nagorno-Karabakh and Syria/Iraq Aftermaths.

(2012)

During the 1988 - 1994 Nagorno-Karabakh conflict nearly 360.000 refugees - ethnic Armenians - fled Azerbaijan to Armenia. An even higher number - over 600.000 - of Azeris were driven from Armenia and Karabakh. The government of Armenia provided the refugees from Azerbaijan with rooms in former public administrative buildings not in function after the collapse of USSR - e.g. abandoned hotels, hostels, schools or kindergartens. Many refugees have acquired Armenian citizenship, others decided to hold their refugee status. Many died here as they grew older, others had success to escape the situation - but too many still survive in poor social and living conditions, and that since 20-23 years. Additionally, many ethnic Armenians fled Iraq and more recently, Syria. These ethnic Armenians are descendants of those driven from West Armenia during the 1915 Armenian Genocide, now returning to Armenia proper.The image was taken in 2011 during a photo project in collaboration with UNHCR Armenia and Helsinki Citizens' Assembly Vanadzor.

Dignity

(2012)

In the autumn of 2012 I worked with UNDPI Armenia on a small photo project about children with Special Needs in the orphanage Kharberd near Yerevan, Armenia, about 280 children live under hard conditions hard to imagine for outsiders. Disabled, left behind by their parents and forgotten by society, they depend on the work of a few motivated and dedicated people - nurses, doctors, pedagogues and social workers. The goal of the photo project was to show the children and their dignity, despite their daily struggles and the situation they live in. This image is for me the best of the series, because it displays exactly what I wanted to show.

Kharberd, Yerevan, Armenia; 09.10.2012

Kharberd, Yerevan, Armenia; 09.10.2012

Children in an IDP school, Kutaisi (Georgia)

(2011)

In autumn 2011 I worked with the Norwegian and Danish Refugee Councils on a photo project about internally displaced people (IDP) in Georgia, following the conflict in Abkhazia. I also worked with educational projects and children, both in Georgia and in Abkhazia. What I took away from this work is that children are the same on both side of the conflict – playful, innocent, curious. They are still far away from politics, ethical questions and the issue of status of the Abkhazia, and they gave me hope that this seemingly endless conflict someday will be solved for good.

(Published as Leica Fotografie International Photo Story)

(Published as Leica Fotografie International Photo Story)

Ararat

(2011)

The legacy of history hangs in the air as two policemen stroll over the pavement at another hot and sunny summer day in Armenia’s capital Yerevan. They patrol the grounds of the Tsitsernakaberd memorial, dedicated to the Armenian genocide victims of 1915. Armenia’s holy mountain Ararat – now firmly in Anatolia - looms in the back, as a reminder of a dark and nebulous stretch of history. Every time I am in Armenia, no matter how sunny it is, beautiful Ararat seems to spread a somber aura over the country. Will I ever be able to visit Armenia or Turkey and see Ararat as worthy holy and religious mountain, signifying respect, dialogue and forgiveness?

(Published as Leica Fotografie International Photo Story)

(Published as Leica Fotografie International Photo Story)